This is a slightly extended version of a piece that Keith Telly Topping wrote for Shivers magazine in 2002 and which he has always felt worked quite well:

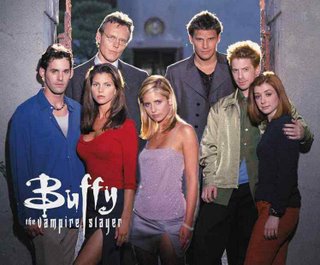

This is a slightly extended version of a piece that Keith Telly Topping wrote for Shivers magazine in 2002 and which he has always felt worked quite well:Buffy The Vampire Slayer has, effectively, rewritten the entire Fantasy/Horror rule-book over the last six years. Keith Topping, the author of the best-selling unofficial Buffy guide The Complete Slayer, looks at why this needed to be done and how it was achieved.

‘I watched a lot of horror movies as a child,’ Joss Whedon told The Big Breakfast in 1999. ‘I saw all these blonde women going down dark alleys and getting killed. I felt really bad for them. I wanted, just for once, one of them to kill the monster for a change. So I came up with Buffy.’

Whether Buffy The Vampire Slayer, conceptualised when Joss Whedon was just twenty one years of age, should be regarded as an example the writer's precocious talent or as a triumph for his impressive persuasive skills remain unclear. But the very fact that the concept (additively silly title and all) ever made it beyond its initial one-line pitch - 'teenage airhead schoolgirl fights vampires in the San Fernando Valley' - in the cut-throat world of the Hollywood system more than suggests the latter.

Comedy and vampirism may seem strange bedfellows but Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) showed that such a merging of seemingly incompatible genres was entirely possible. Indeed, as the critic RW Johnson noted in New Society in 1982, ‘we have actually got round to really funny films about vampires - not burlesques, which refuse to take the myth seriously, but comedies which accept the myth head on, and still laugh at it.’ In the 1980s, at the very moment when the vampire novel was attempting to become a serious literary subgenre with the success of Anne Rice’s novels, a slew of teenage vampire movies were being made in America. Mostly low-budget, often sneered at by ‘serious’ movie critics who regarded the horror motif as unworthy of proper study and equally loathed by old-time horror fans because they didn't include capes, castles and bats, from Fright Night, Once Bitten and Beverly Hills Vamp it’s a relatively short step to the movie version of Buffy The Vampire Slayer, a critical and artistic failure upon its release in 1992.

Four years later and Whedon, now a much sought-after Hollywood scriptwriter with an Oscar nomination for his work on Toy Story and script-doctor non-credits on Speed and Twister under his belt, was asked to revive the Buffy format for television. Nobody seriously expected that it would last more than twenty episodes. The title, alone, was ridiculous.

Whilst a lifelong fan of horror movies and comics, and acknowledging the influence of two stylistically fascinating modernist vampire films (Near Dark and, especially, The Lost Boys) on his concept, Whedon was smart enough to realise that the series could not live by vampires alone. The original movie script had started life as a witty pastiche on the real horrors of the high school years: about alienation, loneliness, isolation, peer pressure and parental expectations. 'For me, high school pretty much was a horror movie,' noted Whedon, who attended New York's prestige Riverdale School. 'Girls wouldn't so much as poke me with a stick.' So, when the chance came to expand his movie concept into a weekly TV series, Whedon decided that he would make the series 'a metaphor for how lousy my high-school years were. But, from episode three onwards, vampires were to be only a part of the mix.

'Buffy has all the classic monsters: vampires, werewolves and mummies,' Whedon told BBC Online in 2000. It has also included in its bestiary of terrors a plethora of demons and witches (both good and very, very bad), hyena spirits, insect creatures, malevolent robots, ghosts, invisible girls, fairy-tale monsters, zombies, incubi, succubae, pan-dimensional Gods and even the odd alien slug. A veritable carnival of horrors. As Rupert Giles tells the heroine in the series' pilot episode, Welcome To The Hellmouth: 'Everything you've ever dreaded was under your bed, but told yourself couldn't be by the light of day. They’re all real.'

Whedon's inspiration for Buffy involved not only his own experiences at school, but also the woes of others. ‘When I got together with my writing team, I asked them “What was your favourite horror movie? What was the most embarrassing thing that ever happened to you? How can we combine the two?”’ Like many modern fantasy television series (Stargate SG-1 and The X-Files are two other excellent contemporary examples), Buffy’s writers seem to revel in knowingly sampling exterior texts into their work. That is, to wear their source material like a badge of authenticity and ask, ‘hey, what happens if you take a bit of Dracula, Prince Of Darkness and bit of Salem’s Lot and a bit of A Clockwork Orange and mix ‘em all up?’ They do this, seemingly, in the certain knowledge that their audience are sussed enough to know what they’re watching an homage to. And to celebrate that.

Intellectual parallelograms to classic monster movies like The Bride Of Frankenstein (Some Assembly Required) and The Curse Of The Werewolf (Phases) and of modern horror fables such as Hellraiser (Hush), Nightmare On Elm Street (Killed By Death) and Children Of The Corn (Older, & Far Away) are cleverly combined in Buffy. It's a breathless mix of knowing allusions, visual references and outright name-checks. (The character of Buffy's friend Xander Harris, for example, seems to have an encyclopaedic horror knowledge that matches Whedon's own.)

What’s more to the point is that the show is made for an audience who, Whedon and his writers obviously believe, have pretty much the same video and comics collection and the same willingness to explore a favourite genre as they, themselves, do. This, kids, is what happens when the fanboys (and, in Jane Espenson and Marti Noxon’s case, the fangirls) take over running the asylum. We get what we’ve always wanted. Our kind of show.

Even in its early days, Buffy seemed to know exactly what the viewers wanted to see from it. Thus, within weeks of the show beginning we had an episode like ‘The Witch’, a beautifully fashioned combination of quite ludicrous body-swap shenanigans and Carrie-style high school supernatural horror full of self-combusting cheerleaders and frustrated sexual yearning. After this, the two key conceptual episodes of the first season were Angel, the roots of which lay deep in the doomed Byronic Gothic romance backstory of Coppola's Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the remarkable Out Of Mind, Out Of Sight, a delicious revenge-saga which used elements from The Invisible Man, Hallow'een and The House That Screamed to fashion a story about the crushing cruelty of loneliness.

The Buffy production team, clearly, had enough wits about them to realise that a generic patchwork can be effective both for those viewers who recognise the origins of what they’re watching and for those too young to do so, but who don’t care anyway because, to them, it’s all new. An episode like Ted ably demonstrates this - in other hands, desperately faux-naïf - duality perfectly. It’s almost the definitive Buffy-as-teenage-horror tale in a series in which hyena-kids, vampires and witches are de rigueur as opposed to real life where we have bullies and abusive parents instead. Whedon and his writers use the clichés of the horror genre as a metaphor for the terrors of being a teenager (thus Buffy’s divorced mother’s new boyfriend is a violent robot because, to a teenage girl, that’s exactly how a prospective stepfather would appear).

Put simply, in Buffy the obsessions and fears of teenagers are, literally, made flesh. This is, largely, what got the show its audience from day one.

Many of Buffy’s viewers - far more than most other series could dream about - are hip to the metaphors at the heart of each episode, and of the series itself. The subtext stuff: ‘Be careful what you wish for, it might just come true,’ ‘I had sex with my boyfriend and he turned into a monster,’ ‘no-one ever seems to notice me,’ ‘the only way I can achieve anything is through a senseless random act of violence.’ This enables them to stay a step ahead of the characterisation so it was no surprise to the audience when, for example, Cordelia suddenly metamorphosed from a hollow two-dimensional bad girl archetype into something considerably deeper. Or when Willow evolved and blossomed.

Even more impressively, these viewers connected with the series’ sly and pointed observations on sexuality, the warming comfort of denial, the pleasure of guilt and the thrill of punishment and, most obviously, the joy of redemption (Angel, Spike, Wesley and, especially, Faith). The audience got with the programme, basically. And, as a direct consequence, the programme got with them.

By its third season Buffy was still doing classy tributes to horror favourites of the past (Dr Jekyll &Mr Hyde in Beauty & The Beasts, The Twins Of Evil in Gingerbread, The Dead Zone in Earshot). But, by now, the show was confident enough to start subverting these knowing glances. In episodes like The Zeppo and Homecoming they both paid tribute to, and also laughed at, the sheer absurdity of much of the horror tradition. And they took the audience to very brink of parody in The Prom wherein the episode's protagonist, who intends to release Hellhounds on the Sunnydale High prom night, has his own video collection of the movies that inspired the episode sitting on top of his TV when Buffy comes bursting in on him. There was clever subversion, too, in Fear Itself, an episode about the schlock of teenage Hallow'een parties in which a clichéd ‘haunted house of horror’ becomes far less comfortable than one might have expected.

It’s probably the season four episode, Hush that will be Buffy’s most lasting legacy to the genre and past, present and future. It’s the one that, in fifteen years time, the next generation of horror fans will be talking about in reverential terms the way that fans of my age do about Trilogy Of Terror or certain episodes of Hammer House Of Horror or Doctor Who. Joss Whedon wanted to create the modern day equivalent of a Brothers Grimm nightmare in The Gentlemen. A combination of all of the darkest and scariest things from the darkest and scariest places in the corners of his own, and his audiences, mind. Whedon had specific ideas about what his critical summation of all that is horrible should look like. ‘They came from Nosferatu (both the Max Shreck and Klaus Kinski versions), Dark City, Hellraiser, Grimm’' Fairy Tales, The Seventh Seal. From many storybooks, silent movies and horror movies and many nightmares. And Mr Burns from The Simpsons,’ he noted. And, indeed, they did. They were terrifying.

Perhaps the best example of Buffy’s deliciously Dionysian approach to traditional horror conceits is in its treatment of vampirism, per se. Taking a cue from several modernist texts, and with an extremely healthy disregard for the depressingly traditionalist approach of, for example, the works of Anne Rice (notice how dismissive on the subject of that particular author Spike is in School Hard), Buffy sees vampirism as less of a plague of evil and more as something akin to a sexually transmitted disease. Note, for example, how Buffy herself describes the process of a person being turned into a vampire as ‘a big sucking thing’ in one early episode.

The subliminal link between vampirism and sex is nothing new, of course, but in Buffy that link is less sensual and erotic and more like an addiction. In this regard, the series is much closer to something like Simon Raven's classic 1960 vampire novel Doctors Wear Scarlet than to Dracula. Yet, ironically, when the old Count himself finally turned up for a somewhat surprise appearance in the season five opener, the series attitude to this horror icon wavered somewhat uncomfortably (yet very amusingly) between arrogant dismissal (Buffy knowing that the dead Dracula will return because 'I’ve seen all your movies') to the clever incorporation of elements of the Dracula myth within its own framework. (Giles's meeting with The Three Sisters echoing Jonathan Harker's decent in Stoker’s novel; Nicholas Brendon's uncanny impression of Dwight Frye's Renton from Tod Browing’s movie version.) The message here seems to be, we may take the mickey at times, but at the end of the day we’re still fans at heart.

The horror that Buffy presents as its public face is a critical nexus of numerous styles and vogues. Gothic romance, urban alienation, myth and fantasy, postmodern sampling of exterior texts. All filtered through a charming gauze of Californian cynicism. If all this blather makes it sound like a dry and academic exercise in creating a cool TV show for kids of all ages by ripping-off all of the best bits of the movies that we’ve enjoyed over the last seventy years, then that damns Buffy with the faintest praise possible. Far less than it deserves.

What Joss Whedon and his writers have done with the horror genre is to perform a surgical examination of what, exactly, makes it tick. Not an autopsy, because the horror genre is as alive as its ever been, but a poke through the entrails to find new ways to scare people. They’ve come up with some absolute crackers - killing the heroine’s mother (The Body) and, subsequently, the heroine herself (The Gift) are brilliant examples. Then, they resurrected her and dragged her, bodily, out of heaven by clueless friends who were just trying to help (Bargaining).

The recently completed sixth season had its moments of looking backwards to where we've come from, but most of its energies were concentrated on a new kind of horror to the Buffy oeuvre and the wider genre. The horror of, reluctantly, having to grow up fast. That’s one we all have to face and it never gets any easier.